The sole printed reference book for calculator collectors, "The Complete Collector's Guide to Pocket Calculators" (Ball & Flamm, 1997) states on page 16 that, as of that time,

"Previously unknown models continue to surface, adding to the excitement."

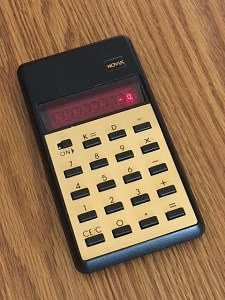

That appears to be true roughly two decades later, as the RES Mark I seen here is the only known example; it appears nowhere on the net*, is not in the Ball & Flamm book, and has no references anywhere that we can find. For the moment, this calculator is the only known example.

RES stands for Radiant Energy Systems, a California company known to have been working on developing methods to improve the manufacture of printed integrated circuits in the early 1970's but about which not much else is known. California business records show that this company existed only for the ten year period 1969-1979, making it yet another one of that phalanx of companies which got in with the rush of IC's, calculators and the like and which also did not survive the decade. The calculator in question was won on auction this year, and came complete with box and sleeve, shipping (cardboard) cover and instruction book. It is of interest to note that the label "Made in Hong Kong" is a sticker, applied only to the one side of the box - the other being identically printed but omitting the sticker.

The calculator, which is serial number 010141, is an eight digit machine having memory, as well as memory exchange, sign change and percent functions. The calculator has strange, small, clicky keys which have raised edges and stickers in their centers. The calculator operates on a 9V battery or an AC adapter, which is not included and whose model is not referenced.

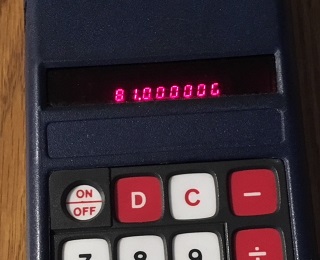

Like many early calculators this model does not clear on startup and also has the negative zero bug.

|

| Startup gobbledygook on RES Mark I screen before clearing. |

The display of the RES Mark I will shut down to just a "-" in the center of the display after 15 seconds of no use; the EX key is depressed twice to restore the display. (This simply exchanges the previous keyboard entry; use of the C key will restore the display as well but clears the operations.) The clear key on this machine acts as 'clear entry' on the first depression and 'clear all' on the second. As mentioned, EX swaps the last entered figure with that previous for inspection of possible error.

An automatic constant feature is included on the machine, it being the last entered value in a calculation. For example to use the number 37 in a set of calculations as a constant, the operator might first enter "100" and then hit "+" and then "37" and then "=". The number 37 is automatically the constant; if the operator then presses "10" and then "=" the calculator will toss the previous final result, add the new entry 10 to the constant 37 and display 47.

Some collector references such as Ball & Flamm and some websites do feature some other known Radiant Energy Systems calculators, but none is this model and none matches it. We're quite lucky for now to have an "only one known" calculator, although prior collecting experience tells us that sometime soon another will come up. What's interesting now is that even this long after the end of the classic era of early calculators (1971-1979) there are still unknowns like this that can pop up!

* - The RES Mark I pictured on Serge Devidts' "Calcuseum" website is this example; apparently the photos were taken from the auction page. RES Mark I serial 010141 is in the Will Davis collection.